In this post we’ll look at how to take a regular command-line program, script, or HTTP server and convert it into a serverless function, along with some of the benefits of doing so.

I just got off a call with a Director of IT for a non-profit in North Carolina. He told me that he had around 40 Python scripts that he kept on his laptop, and ran manually from time to time. He also wanted to make one of them available to around 600 employees to submit an annual report, for central processing. You could think of this collection of code as traditional “back office” processing - the parts that make the system work. He found out about functions, and thought it would be easier to manage than writing an API and deploying it to a cloud VM.

This post is for you, if like him, want to get your code into production in a quick and reliable way, without getting bogged down with making choices about infra, hosting, monitoring, and security. Serverless covers most of this for you, so you can focus on solving the problem at hand.

We’ll first look at the concept of a function, how they run on cloud solutions, and how self-hosted can sometimes be a better option. We’ll then go through the mechanics of input, output, configuration, state, dealing with files and secrets, and there’ll be lots of code examples along the way.

What is a Serverless Function?

Functions are stateless, ephemeral, and event-driven, meaning they can be triggered by various events such as HTTP requests, file uploads, or database changes. Developers can focus on writing code, rather than managing servers.

The concept originated from the cloud, being popularised by the AWS Lambda service and is now widely available from other providers such as Google Cloud Functions and Azure Functions. Lambda is a SaaS service designed to serve hundreds of thousands of tenants in an efficient, and cost-effective manner.

In order to run a reliable and profitable service, AWS had to implement a stringent set of limits, and capabilities, which can leave developers feeling frustrated when they want to do something outside of the set limits, such as running an execution over an extended period of time, running on-premises, deploying existing code to another cloud provider, or even using a GPU.

Functions also offer benefits over traditional server-based applications by simplifying packaging, deployment, and management.

So what if we could take the concept of functions, but solve for some of these issues?

How OpenFaaS helps

OpenFaaS takes the familiar model of functions, and makes them portable, and configurable. You can now run them not only on AWS using a service like AWS EKS, but on Google Cloud, Azure, Oracle Cloud, and even on-premises with your own hardware.

How? The paradigm shifts when you self-host functions using containers and Kubernetes. Where once you were limited to a 15 minute timeout, you can now run an execution for hours, or even days. Where you couldn’t use a GPU, you can now allocate one or more to a function, or even package a popular LLM such as Deepseek to serve requests.

It also improves the developer experience. You can install the same platform on your machine and test your functions fully on your own machine, with a fast feedback loop, before publishing them to production.

You’re also not tied to a specific set of events. Instead of being limited to AWS SNS or AWS SQS, you can start consuming events from Apache Kafka, or RabbitMQ - or just receive HTTP requests. The options are vast and extensible

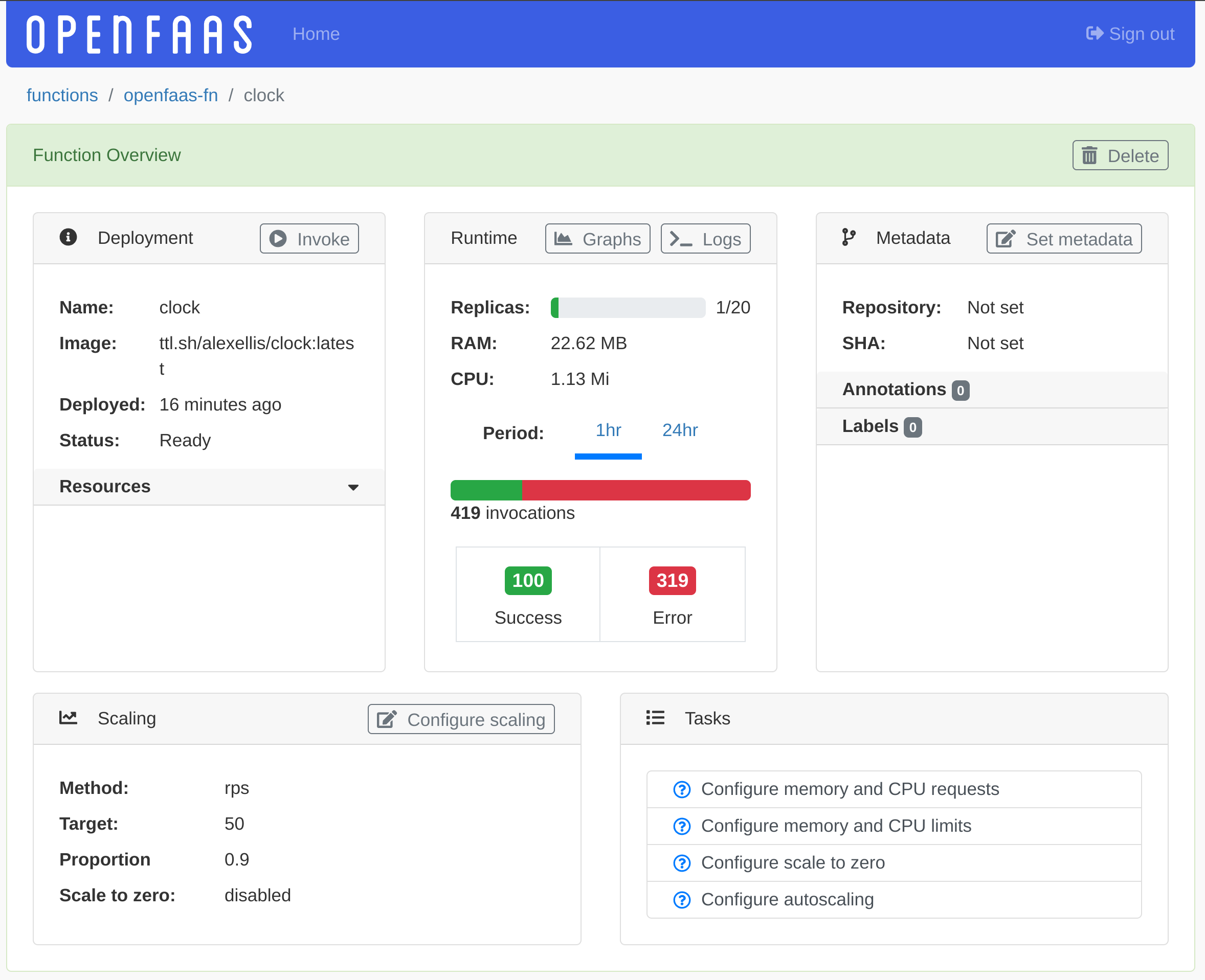

Once your functions are deployed, you can monitor them through the OpenFaaS Dashboard, and Grafana dashboards for latency, throughput, and error rate.

The autoscaler helps your code respond to spikes in demand, and scale to zero can keep your costs and utilization down when demand is low.

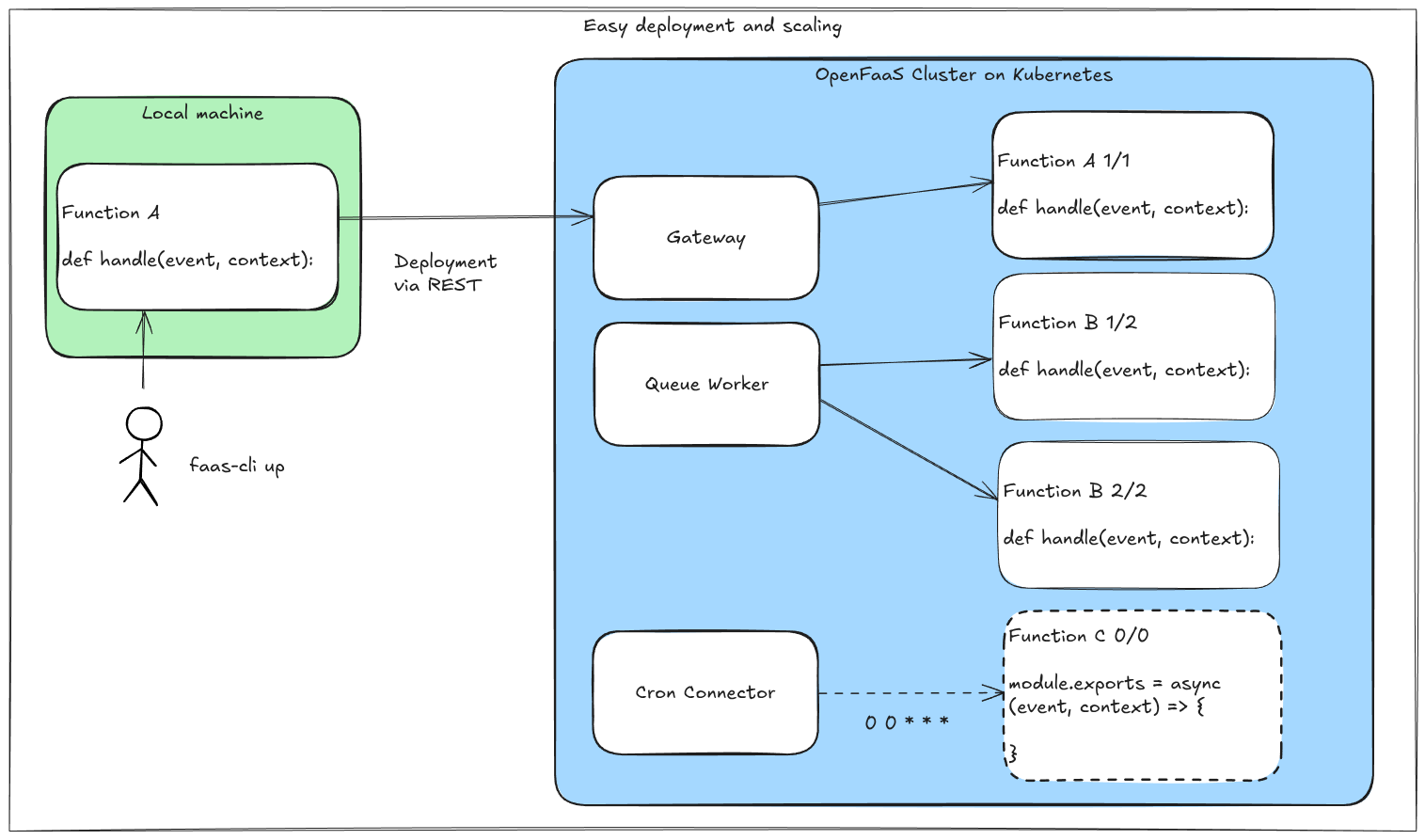

In the above conceptual overview, we have the following:

- A user working on his local machine runs

faas-cli upto deploy a function - A synchronous invocation is in progress via the gateway to Function A - written in Python

- Two asynchronous invocations are in progress to Function B which has two replicas - traffic is being load balanced across the two

- Function C is scaled down to zero replicas, and will be invoked by the Cron Connector at midnight every day

Once OpenFaaS is installed to a Kubernetes cluster or to a VM using OpenFaaS Edge, then adding a new function is as simple as running faas-cli new followed by faas-cli up. It’ll then be managed, scaled, and monitored for you by the platform, and can be invoked by any number of different triggers.

How do traditional programs work?

Traditional programs can be divided into two categories:

- One-shot CLIs - start up, take some configuration and work parameters, output, then exit - think of something like

curlorpsql - Long-lived daemons - start up, often binding to a TCP port, then wait for requests - think of something like

nginxorpostgres

We will explore options for configuration, inputs, outputs, and state and storage for both types of programs and how they can be converted into functions.

The examples will be a mixture of Go, Node, and Python.

Listening on a port

In the case of a long-lived daemon, traditional programs will often listen to HTTP requests on a given TCP port.

This is done automatically in OpenFaaS, and is hidden as part of the template’s entrypoint implementation.

Every function once deployed will get its own path on the OpenFaaS gateway, and will be able to receive HTTP requests both synchronously and asynchronously.

Here are a few examples of how to start up a HTTP server in various languages, in regular CLI programs:

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello, world!")

})

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil))

}

Or if we’d used Flask:

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def hello_world():

return 'Hello, World!'

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=8080)

Or if we’d used Node.js and Express:

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.send('Hello, World!');

});

app.listen(8080, () => {

console.log('Server is running on port 8080');

});

With OpenFaaS templates, this is already done for us, so we focus on the logic of the program. How to handle a request and return a response.

The template for Go golang-middleware uses a regular http.HandlerFunc to handle the request.

Most of the other templates use a similar pattern, but with a “context” and “request” object used in a very similar way.

package function

import (

"fmt"

"io"

"net/http"

)

func Handle(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var input []byte

if r.Body != nil {

defer r.Body.Close()

body, _ := io.ReadAll(r.Body)

input = body

}

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

w.Write([]byte(fmt.Sprintf("Body: %s", string(input))))

}

To generate the function, you can run the following replacing the variable in OPENFAAS_PREFIX with your own container registry and account.

export OPENFAAS_PREFIX=ttl.sh/openfaas-test

faas-cli new --lang=golang-middleware http-to-json

faas-cli up

Then invoke the function with curl or using the OpenFaaS CLI:

curl http://127.0.0.1:8080/function/http-to-json

faas-cli invoke http-to-json

Flags and arguments

Flags and arguments are passed to the program at start-up to configure its behaviour or to give the input for the task.

If you had a program which took an URL as an argument, then made a HTTP request and printed the response back, it’d perhaps look like this:

./http-to-json https://hacker-news.firebaseio.com/v0/topstories.json

In OpenFaaS, these need to be read via the handler within the function.

For example, in Go with the golang-middleware template, we’d write:

package function

import (

"io"

"net/http"

"net/url"

)

func Handle(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.Body != nil {

defer r.Body.Close()

}

parseUrlV := r.Header.Get("X-Parse-Url")

parseUrl, err := url.Parse(parseUrlV)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Invalid URL", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

res, err := http.Get(parseUrl.String())

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Error fetching URL", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

defer res.Body.Close()

if res.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

http.Error(w, "Error fetching URL", res.StatusCode)

return

}

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

io.Copy(w, res.Body)

}

In Go, we’re able to use r.Header.Get to read the header value from the request. In this case, we are using X-Parse-Url as the header name.

In Python, we use event.headers.get('X-Parse-Url') to read the header value from the request.

And then in Node.js, we’d use event.headers['X-Parse-Url'] to read the header value from the request.

Once deployed, our function will get its own URL and we can call it with a simple HTTP request:

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/function/http-to-json \

-H "X-Parse-Url: https://hacker-news.firebaseio.com/v0/topstories.json"

This is a simple example, but it shows how we can take a program that takes an argument and convert it into a function that takes an HTTP request.

The faas-cli can also be used to invoke the function:

echo | faas-cli invoke http-to-json \

-H "X-Parse-Url=https://hacker-news.firebaseio.com/v0/topstories.json"

The faas-cli command requires an input from STDIN, so we can either run the command and give an input, or pass an empty input with echo.

Environment variables for configuration

Environment variables are used for static configuration for many kinds of programs, including HTTP servers. You may be setting an option for log verbosity, or the URL for a dataset that is needed for the program to operate.

OpenFaaS makes a distinction between confidential and non-confidential environment variables. Let’s start with non-confidential ones, also known as “configuration”.

Typically, if we wanted to run our previous program with higher verbosity, it may look like this:

export VERBOSE=1

./http-to-json https://hacker-news.firebaseio.com/v0/topstories.json

In OpenFaaS, we can set the environment variable in the stack.yml file:

version: 1.0

provider:

name: openfaas

gateway: http://127.0.0.1:8080

functions:

flags:

lang: golang-middleware

handler: ./flags

image: ttl.sh/flags:latest

+ environment:

+ VERBOSE: "1"

Alternatively, we can supply the name of an environment file. This is useful for when you want to deploy the same function to multiple different environments or regions, and just want to change the environment variables for each one.

Create a dev.env file with the following contents:

VERBOSE=1

Then, in the stack.yml file, we can reference the file:

version: 1.0

provider:

name: openfaas

gateway: http://127.0.0.1:8080

functions:

flags:

lang: golang-middleware

handler: ./flags

image: ttl.sh/flags:latest

+ environment_file:

+ - dev.env

Then, if you needed to replace the name of the environment file, you could do so in the stack.yml file using environment variables.

functions:

flags:

lang: golang-middleware

handler: ./flags

image: ttl.sh/flags:latest

environment_file:

+ - ${ENV_FILE:-dev.env}

Then you have the option to set the environment variable ENV_FILE to the name of the file you want to use.

# Deploy with the development configuration

faas-cli up

# Deploy with the staging configuration

ENV_FILE=staging.env faas-cli up

# Deploy with the production configuration

ENV_FILE=prod.env faas-cli up

Here’s how we can read the environment variable in Go:

func Handle(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.Body != nil {

defer r.Body.Close()

}

parseUrlV := r.Header.Get("X-Parse-Url")

+ if v, ok := os.LookupEnv("VERBOSE"); ok {

+ if v == "1" {

+ log.Printf(`Value of "X-Parse-Url": %s`, parseUrlV)

+ }

+ }

parseUrl, err := url.Parse(parseUrlV)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Invalid URL", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

res, err := http.Get(parseUrl.String())

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Error fetching URL", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

defer res.Body.Close()

if res.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

http.Error(w, "Error fetching URL", res.StatusCode)

return

}

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

io.Copy(w, res.Body)

}

In Python, we’d use os.Getenv to read the environment variable.

In Node.js, we’d use process.env.VARIABLE_NAME to read the environment variable.

In addition to headers, the HTTP Path, Query String and Body can also be read and parsed by your function.

Reading files from the filesystem

A classic use-case for Go programs is to read a Go template from the filesystem, and to use it to generate some dynamic content.

With a regular CLI program, we’d do something like this:

func main() {

content, err := os.ReadFile("template.tmpl")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to read template: %s", err)

}

fmt.Println(string(content))

}

One thing you must never do in a function is to call log.Fatal or os.Exit as this will crash the function, and cause it to restart.

Instead, you should return a HTTP error response, and if you think it makes sense, also log an error message. Anything logged to stdout or stderr can be viewed via faas-cli logs or in the OpenFaaS Dashboard.

In Go, we can use the http.Error function to return a HTTP error response.

http.Error(w, "Failed to read template", http.StatusInternalServerError)

Most OpenFaaS templates support bundling files in a folder named static inside of the function’s source-code directory.

faas-cli new --lang=golang-middleware tmpl

mkdir -p tmpl/static

cat <<EOF > tmpl/static/welcome.html.tpl

<html>

Hello, {{.Name}}

</html>

EOF

Write a program that reads a Go HTML template and uses it to generate some dynamic content.

package function

import (

"fmt"

"html/template"

"io"

"net/http"

"strings"

)

const templatePath = "./static/welcome.html.tpl"

var welcomeTemplate *template.Template

func init() {

tpl, err := template.ParseFiles(templatePath)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

welcomeTemplate = tpl

}

type WelcomeRequest struct {

Name string

}

func Handle(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var input []byte

if r.Body != nil {

defer r.Body.Close()

body, _ := io.ReadAll(r.Body)

input = body

}

req := WelcomeRequest{Name: strings.TrimSpace(string(input))}

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "text/html")

if err := welcomeTemplate.Execute(w, req); err != nil {

http.Error(w, fmt.Sprintf("Error executing template: %s ", err), http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

}

Notice that we read the template from disk only once at start-up, and then use it to generate the content for each request. We can use func init() for this in Go.

For languages and templates that do not support running code outside of the handler, you can assign the value on the first request, and then use it for subsequent requests.

I got the following response from curl http://127.0.0.1:8080/function/tmpl --data "Alex":

<html>

Hello, Alex

</html>

As a bonus, Go unlike other languages has built-in support for embedding files directly into the executable via the embed package. This is a good option for small files like HTML templates, but less so for larger binaries which would increase the size of the binary.

OpenFaaS uses container images, and so keeping our files in the static folder means we can take better advantage of layer caching, sending only the changed files rather than the binary to the registry when we change these files.

Writing state and files

Functions are stateless and you shouldn’t assume that state or files set up by one request will be available in the future.

If you want to take in a file in the HTTP body, and store it on disk for processing, then you can do so in the /tmp directory.

Use-cases may be video conversion, image processing, encryption/decryption, segmentation, or uploading to AWS S3, Google Cloud Storage, or Azure Blob Storage.

faas-cli new --lang=python3-http store-file

import os

import tempfile

def handle(event, context):

tmp_dir = tempfile.mkdtemp()

tmp_file = os.path.join(tmp_dir, "request_body")

with open(tmp_file, "wb") as f:

f.write(event.body)

f.flush()

f.close()

file_size = os.path.getsize(tmp_file)

print(f"File size: {file_size}")

os.remove(tmp_file)

os.rmdir(tmp_dir)

return {

"statusCode": 200,

"body": f"Size: {file_size}"

}

Now invoke the function with a file:

curl http://127.0.0.1:8080/function/store-file \

-X POST \

-H "Content-Type: application/octet-stream" \

--data-binary @./stack.yaml

I got: Size: 347

Consuming secrets

OpenFaaS uses the built-in Kubernetes secret store for storing sensitive information such as connection strings, API keys, and passwords.

You can create a secret in two ways - either from a literal string on the command line, or from a file.

faas-cli secret create api-key --from-literal "my-secret"

Note the two spaces preceding the command, this ensures bash will not store the command in the history, which would expose the secret.

Alternatively use a file:

echo "my-secret" > secret.txt

faas-cli secret create api-key --from-file secret.txt

faas-cli new --lang python3-http protected-fn

Then, in the stack.yml file, we can request them using the name of the secret i.e. api-key:

version: 1.0

provider:

name: openfaas

gateway: http://127.0.0.1:8080

functions:

protected-fn:

lang: python3-http

handler: ./protected-fn

image: protected-fn:latest

+ secrets:

+ - api-key

In the handler, you can now read the secret from the filesystem. These files will be mounted in /var/openfaas/secrets/ directory and will be available to the function.

def handle(event, context):

with open("/var/openfaas/secrets/api-key", "r") as f:

api_key = f.read().strip()

if event.headers.get("Authorization") != f"Bearer {api_key}":

return {

"statusCode": 401,

"body": "Unauthorized"

}

return {

"statusCode": 200,

"body": "Hello from OpenFaaS!"

}

Example of invoking the function with curl:

$ curl -i --silent http://127.0.0.1:8080/function/protected-fn

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

Content-Length: 12

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Date: Mon, 24 Mar 2025 10:02:07 GMT

Server: waitress

X-Duration-Seconds: 0.000827

Unauthorized

$ curl -i --silent http://127.0.0.1:8080/function/protected-fn \

-H "Authorization: Bearer my-secret"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 20

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Date: Mon, 24 Mar 2025 10:05:29 GMT

Server: waitress

X-Duration-Seconds: 0.001077

Hello from OpenFaaS!

External triggers and events

Many people think of functions as being event-driven, however this term is often misused.

It does not mean that functions have to be invoked through a connection to an event broker like Apache Kakfa. It simply means that they are invoked through a trigger, and are short-lived. They cannot invoke themselves or run in the background without an initial event. That event could be a HTTP request.

Along with synchronous and asynchronous HTTP requests, OpenFaaS adds various Event Connectors or “Triggers” for common brokers and queues such as Apache Kafka, RabbitMQ, and AWS SQS.

The most popular and ubiquitous Event Connector is the Cron Connector which invokes functions on a schedule defined in the stack.yml file.

Write a function to print out the current time:

faas-cli new --lang=node20 clock

'use strict'

module.exports = async (event, context) => {

console.log("Time: ", new Date().toISOString())

return context

.status(204)

.succeed("")

}

Now define a cron schedule for the function in the stack.yml file to run every 5 minutes:

clock:

lang: node20

handler: ./clock

image: clock:latest

+ annotations:

+ topic: cron-function

+ schedule: "*/5 * * * *"

Then tail the logs of the function:

$ faas-cli logs clock --follow

Time: 2025-03-24T10:17:00.000Z

Time: 2025-03-24T10:17:05.360Z

Time: 2025-03-24T10:17:10.360Z

A cron schedule is a convenient way to kick off jobs that need to run on an hourly, or daily basis to import or transform data.

Scale to zero

We just saw how a function could be triggered every 5 minutes using a cron schedule. But what if the function is only needed once per day?

Scale to Zero in OpenFaaS is an opt-in feature that allows you to scale your function to zero when it is not needed. For every other function, just leave them as they are and they’ll always have at least 1 replica running meaning you can beat the cold start time seen with cloud-based solutions.

To enable scale to zero, just update the labels in stack.yaml:

clock:

+ labels:

+ com.openfaas.scale.zero: "true"

This function will now get scaled to zero at idle, using the system-wide configured idle period.

We can tune it further on a per-function basis by adding an extra label:

clock:

labels:

com.openfaas.scale.zero: "true"

+ com.openfaas.scale.zero-duration: "10m"

Any function that is scaled to zero will be scaled back up when it gets invoked.

Built-in queue / asynchronous invocations

OpenFaaS has a built-in async queue system that can retry failed requests and invoke a callback URL when the function has finished processing.

The queue-worker is a separate process that pulls in work, and invokes the function asynchronously, some customers use it to handle millions of short-lived requests per day, whilst others use it to process a few very long-running requests to import or sync data.

You don’t have to do anything to make a function asynchronous, you just need to change its URL when you invoke it.

I’m going to limit our clock function so that it can only handle one request at a time:

clock:

environment:

max_inflight: 1

After running faas-cli up again, I use hey to generate 100 synchronous requests to the function:

$ hey -n 100 --method POST http://127.0.0.1:8080/function/clock

Status code distribution:

[204] 24 responses

[429] 76 responses

We can see that 76 requests were rejected with a 429 error, and the remaining 24 requests were successful. That’s because of the max_inflight limit.

Now let’s invoke the function asynchronously instead. All the requests will be accepted, then get invoked in the background by the queue-worker which can retry the requests if a 429 is returned due to the limit.

hey -n 100 --method POST http://127.0.0.1:8080/async-function/clock

We get an immediate response from the gateway with all requests accepted.

Then can see the function being invoked in the logs:

$ faas-cli logs clock --follow

Or you can look at the logs of the queue-worker:

$ kubectl logs -n openfaas deploy/queue-worker |grep "7a73f2cc-c1ed-413b-ae9e-89f8deada9fb"

2025-03-24T11:15:50.977Z Invoke {"callId": "7a73f2cc-c1ed-413b-ae9e-89f8deada9fb", "function": "clock", "delivery": 1}

2025-03-24T11:15:50.979Z Invoked {"callId": "7a73f2cc-c1ed-413b-ae9e-89f8deada9fb", "function": "clock", "delivery": 1, "status": 429, "duration": 0.002106761}

2025-03-24T11:16:10.993Z Invoke {"callId": "7a73f2cc-c1ed-413b-ae9e-89f8deada9fb", "function": "clock", "delivery": 2}

2025-03-24T11:16:11.007Z Invoked {"callId": "7a73f2cc-c1ed-413b-ae9e-89f8deada9fb", "function": "clock", "delivery": 2, "status": 204, "duration": 0.013043763}

The callId field is returned from the /async-function/ endpoint, and is used to track the request through the queue.

We see a few 429 errors, followed by the eventual successful response.

If you want to receive the result of a function, you can pass in the X-Callback-URL header with the URL to receive the result.

$ faas-cli store deploy printer

$ curl -i -X POST http://127.0.0.1:8080/async-function/clock \

-H "X-Callback-URL: http://gateway.openfaas:8080/function/printer"

HTTP/1.1 204 No Content

Connection: keep-alive

Date: Mon, 24 Mar 2025 11:21:52 GMT

Keep-Alive: timeout=5

X-Duration-Seconds: 0.005280

X-Call-Id: 02ec6000-7379-46d0-9280-68076ee8c725

Note the X-Call-Id header, you’ll see it in the logs of the printer function:

$ faas-cli logs printer

Here’s the result:

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z Content-Type=[text/plain]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z Accept-Encoding=[gzip]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z Date=[Mon, 24 Mar 2025 11:21:24 GMT]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z X-Call-Id=[02ec6000-7379-46d0-9280-68076ee8c725]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z X-Duration-Seconds=[0.009309]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z X-Function-Name=[clock]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z X-Function-Status=[204]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z X-Start-Time=[1742815284444741902 1742815284442047146]

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z

2025-03-24T11:21:24Z 2025/03/24 11:21:24 POST / - 202 Accepted - ContentLength: 0B (0.0011s)

Conclusion

In this post we looked at some of the benefits of self-hosted serverless solutions, which are both portable and flexible whilst providing a similar experience to cloud-based solutions.

We then looked at various examples of how to convert from a regular CLI or HTTP daemon into a function that can be deployed to OpenFaaS. There’s much more to explore, but I hope this post gives you a good starting point.

| Feature | Traditional App | OpenFaaS Functions | Cloud-based functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work to add a new program | Considerable | faas-cli new and faas-cli up |

Create via cloud UI or CLI |

| Packaging | Zip files over SFTP/Docker images | Container images | Zip files uploaded to cloud storage or web-based IDE |

| Scale to Zero | No | Yes (opt-in) | Yes (always on) |

| GPU support | No | Yes | Yes (no) |

| Input | Flags, args, env, files | HTTP headers/body | HTTP headers/body |

| Configuration | Files or Environment variables | Environment variables | Environment variables |

| Execution time | Unbounded or long-running | Configurable (no enforced limit) | Limited to 60s or a few minutes |

| Secret handling | Environment variables | Kubernetes secrets / secrets manager | Environment variables / secrets manager |

| Event triggers | Manual work | Built-in connectors (Kafka, AWS, RabbitMQ, cron) or HTTP | Vendor’s proprietary connectors (AWS SQS / AWS S3) |

| Async queue | Manual work | Built-in async queue with retries and callbacks | Vendor’s proprietary async queue |

If you’d like to explore more examples of functions, check out the OpenFaaS templates in the docs.

Kubernetes isn’t the only way to run OpenFaaS - OpenFaaS Edge can run everything you need for relatively low demand and event-driven automation on a single VM.

Connect with us

We run a Weekly Zoom call where you can come along to ask questions, or put us on our toes by requesting with a live demo on the spot!

Also, feel free to reach out to our team for help converting existing APIs, microservices, or scripts into functions.